The discovery of the Sanctuary of Olympia is attributed to the British traveler Richard Chandler in 1766, who was the first to identify the site of the ancient sanctuary—previously known as “Antilalos.”

Interest in the area intensified following the work of J.J. Winckelmann, who envisioned uncovering the treasures of Olympia. Meanwhile, the first professor of archaeology in Greece, Ludwig Ross, attempted unsuccessfully to raise funds for excavations in 1853. The first limited test trenches were conducted in 1829 by the French Scientific Expedition of Moréa under Abel Blouet; these lasted six weeks and brought to light parts of the Temple of Zeus, including metopes that were subsequently moved to the Louvre.

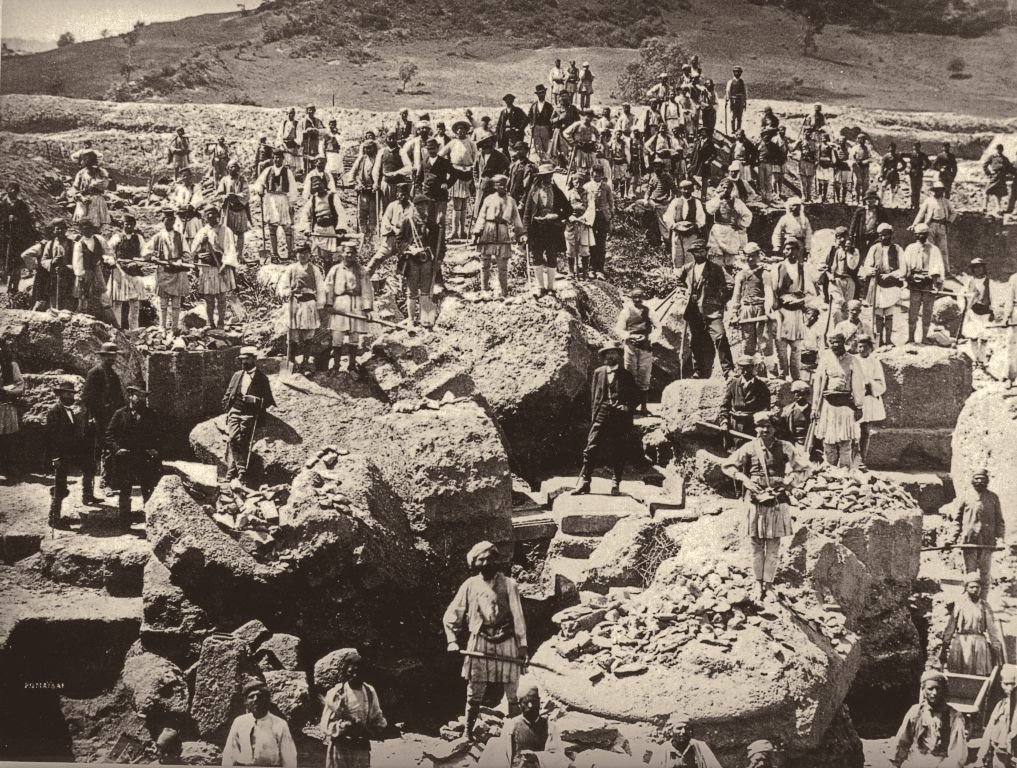

Systematic research began in 1875 by the German Archaeological Institute (DAI), following a formal bilateral agreement between Greece and Prussia in 1874.

The central figure was Ernst Curtius, who secured funding for the project from the German state (approximately 800,000–900,000 gold francs).

During this period, the core of the sanctuary was uncovered, including the Temple of Zeus, the Heraion, the Metroon and the Bouleuterion.

The most important finds were the sculptures of the pediments of the Temple of Zeus, the Nike of Paeonios and the Hermes of Praxiteles.

Curtius was a staunch supporter of the preservation of the finds at their place of discovery, which led to the construction of the first Olympia Museum with a donation from Andreas Syngros in 1888.

Hardships and Human Cost

The 19th-century excavation team faced adverse environmental conditions, with the humid climate and marshes of the Alpheus causing malaria epidemics.

The Greek commissioners, Athanasios and Konstantinos Dimitriadis, recorded in their diaries the isolation, poverty and health problems that tormented them.

Athanasios was forced to resign due to severe paralysis in 1877, while financial difficulties were ongoing.

Furthermore, the lack of permanent housing forced the staff to live in makeshift houses or in the village of Drouva.

Between 1906 and 1929, research continued under the guidance of architect Wilhelm Dörpfeld.

He focused on searching for the sanctuary’s origins, discovering apsidal buildings and prehistoric layers in the area between the Heraion and the Pelopion.

His contribution was crucial for dating the earliest phases of habitation, as he argued that the sanctity of the site dated back long before the first recorded games.

Concurrently, his work at the Theokoleon helped distinguish classical structures from Roman additions.

On the occasion of the 1936 Berlin Olympic Games, a new phase of excavations began under Emil Kunze and Hans Schleif.

The focus shifted to the Ancient Stadium, which was gradually revealed, as well as the South Stoa and the Gymnasium.

This period was marked by an intense sociopolitical impact, as the project was funded directly by order of Adolf Hitler for propaganda purposes, aiming to highlight the ancient Greek spirit as an ideal model.

Work was violently interrupted by World War II.

Excavations resumed in 1952 under Kunze and later Alfred Mallwitz (1972–1984), who discovered Pheidias’ workshop, the Leonidaion, and the northern wall of the Stadium.

From 1984 onwards, under Helmut Kyrieleis, research focused on re-examining the early history of the Altis, with extensive excavations at the Pelopion proving cult activity as early as the 11th century BC.

Recent programs under Ulrich Sinn have focused on the Roman period and Late Antiquity, highlighting the Christian settlement of Olympia.

Today, LiDAR technology, geophysical surveys, and AI are used to digitize data and explore uninvestigated areas of the sanctuary.

Since 2013, the Hellenique Ministry of Culture along with the Ephorate of Antiquities of Ilia, have initiated a challenging endeavour: to completely unearth the gymnasion of Olympia. The project which is procceding in phases, has already brought to light great part of the previously buried east portico of the gymnasion.

The excavations were of immense importance for the formation of the Modern Greek identity, as the connection to the glorious past granted prestige to the newly established state.

The uncovering of the Stadium and the resurgence of interest in athletics led to the revival of the Olympic Games in 1896 by Pierre de Coubertin.

Locally, the excavation acted as a catalyst for development, bringing the railway, hotels, and tourism to the region.

The inclusion of Olympia in the UNESCO World Heritage List in 1989 sealed the site’s universal value.