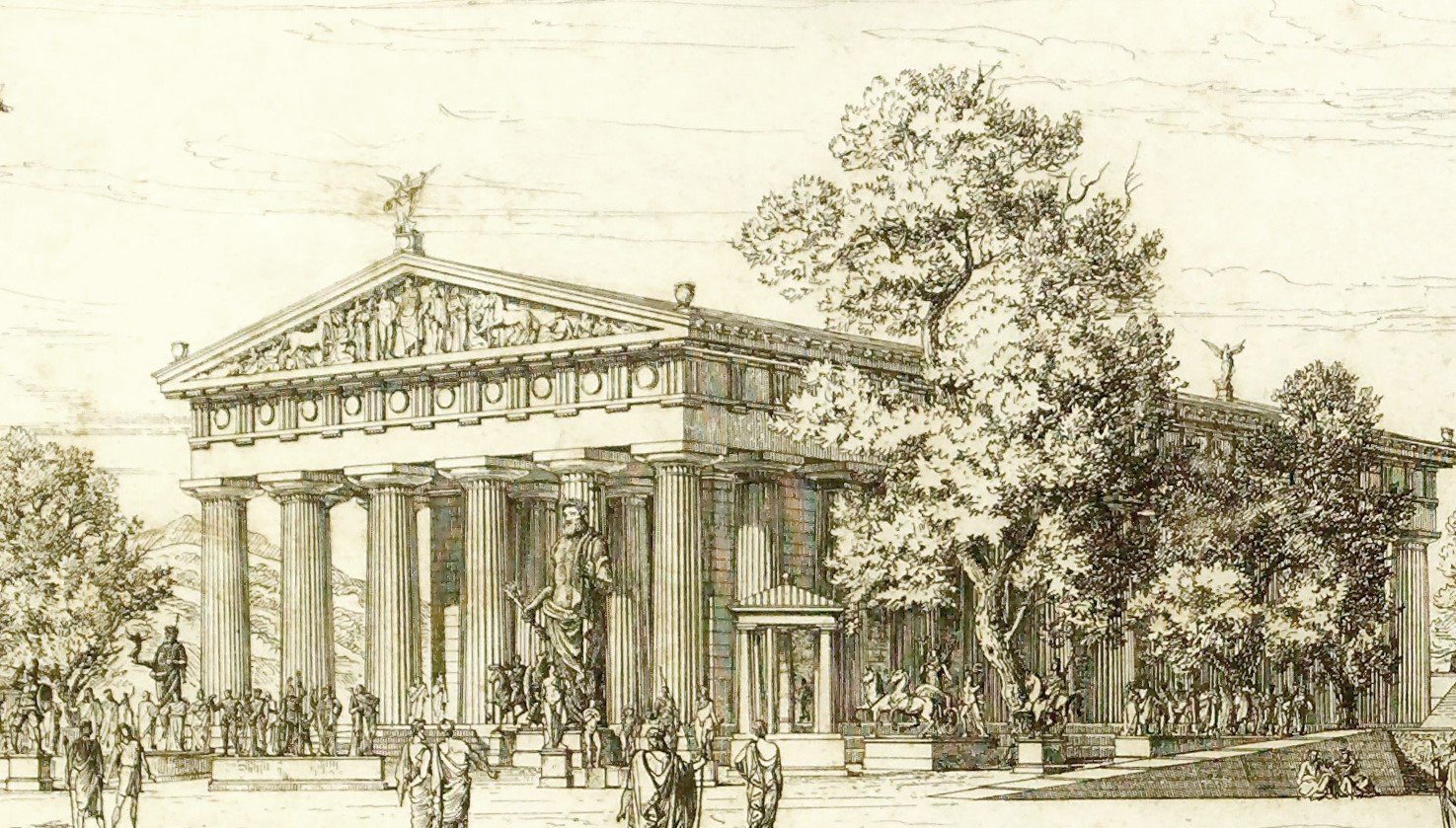

Built between 470 – 456 BCE by the architect Livon of Elis, it occupied the most prominent position within the sacred precinct (the Altis) of Olympia and was made of a coarse local shell-conglomerate covered in fine white stucco.

With six Doric columns across its front and thirteen along each side, its proportions were both grand and harmonious, signalling the importance of the god to whom it was dedicated.

Inside this awe-inspiring temple, the cella (central hall) was divided into three aisles by two rows of slender columns, and above, the roof was clad in marble tiles.

Both the pronaos and the opisthodomos were “distyle in antis” i.e. they have two columns (pillars) placed between two projections (antis) of the side walls. On the floor of the pronaos are preserved the remains of a Hellenistic mosaic with representations of tritons.

The temple functioned not only as a sacred place of worship, but also as a reference center for the ancient Olympic Games: in the pronaos the awarding of the kotinos, the prize of the games, took place.

The great altar of Zeus was located on the side of the temple and not in front, because it pre-existed the temple and was the epicenter of the sanctuary and the Olympic Games.

Athletes and pilgrims converged in the nearby stadium and testify to the fusion of athletic excellence, religious devotion, and communal celebration.

The sculptural decoration of the temple was rich in meaning and symbolism: the eastern pediment depicted the chariot race of Pelops and Oenomaus, while the western pediment depicted the legendary battle of the Lapiths and the Centaurs at the wedding of Peirithus.

On the eastern side of the temple, in the pronaos, above the entrance gate to the main temple and on the western side, on the back wall of the opisthodomos, a frieze consisting of metopes, six on one side and six on the other, depicted in relief the Twelve Labors of Hercules.

The entire sculptural decoration of the temple was recovered at the end of the 19th century after systematic excavations in the sanctuary and is today exhibited in the central hall of the Archaeological Museum of Olympia.

These works are examples of early classical sculpture and have enormous importance for the history of art due to their high artistic value. They also function as indicators of the great cultural and religious prestige of the Sanctuary of Zeus.

Their initial placement high in the temple protected both the sculptures that brought rich colors and the various accessories (metal, wood, etc.) that complemented them. Their precipitation from the temple and the passage of time damaged many of these characteristics and erased some others.

However, despite the losses and damage, the imprint that these masterpieces of the 5th century BC leave each time is still strong today on the psyche of museum visitors, who can easily appreciate the high level and the timeless messages that they transmit.

Perhaps the most celebrated feature of the temple was the great gold-and-ivory statue of Zeus, created by the master sculptor Phidias.

Nearly twelve metres high, the seated figure of Zeus held in his right hand the goddess of Victory, Nike, and in his left a sceptre, mounted on an elaborate throne. This monumental work was widely regarded in antiquity as one of the seven wonders of the world.

Its presence turned the temple into much more than a building—it became a symbol of divine majesty, human artistry, and the very spirit of Olympia.

The Temple of Zeus at Olympia stands as one of ancient Greece’s most significant religious monuments.

Its destruction marked the end of the pagan era and the beginning of centuries of obscurity.

The Destruction Under Theodosius II

In AD 426, Emperor Theodosius II ordered the burning of the temple as part of Christianity’s systematic elimination of pagan worship. By this time, the sanctuary of Olympia had already entered a period of decline—the Olympic Games had been abolished in AD 393 by Theodosius I, ending over a thousand years of athletic and religious tradition.

The Final Collapse

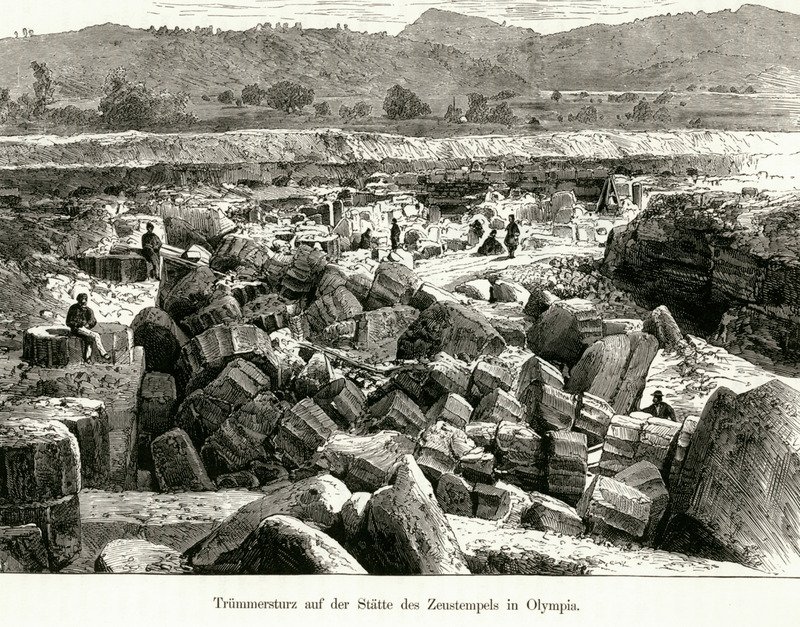

The fire-damaged structure couldn’t withstand the powerful earthquakes of AD 551 and 552 that devastated the eastern Mediterranean.

The temple’s massive Doric columns, standing about 10.5 meters high, toppled and collapsed into ruins.

The site was subsequently buried under layers of silt from the nearby Alpheios and Kladeos rivers, which gradually flooded the sanctuary area, hiding it for over a millennium.

The rediscovery of Olympia emerged from the Enlightenment’s intense fascination with classical antiquity.

Eighteenth-century European intellectuals viewed ancient Greece as the pinnacle of human achievement, spurring scholarly expeditions to document lost monuments.

In this climate, Richard Chandler, an English scholar sponsored by London’s Society of Dilettanti, traveled to Greece between 1764 and 1766. Visiting the buried site of Olympia in 1766, Chandler became the first modern scholar to correctly identify the temple’s remains, relying on careful study of ancient texts, particularly Pausanias’s 2nd-century AD travel guide. His findings, published in Travels in Greece (1776), put Olympia back on the map after more than a millennium of obscurity.

Actual excavation began with the French expedition of 1829, part of the Morea Scientific Mission during Greece’s early independence. The French team removed several metopes depicting the Twelve Labors of Heracles, which were transported to Paris and remain in the Louvre today.

The most comprehensive work was conducted by the German Archaeological Institute beginning in 1875. These systematic excavations uncovered the temple’s ground plan, architectural elements, and much of its sculptural program, employing unprecedented rigor in documentation for the era.

In 2004, the Ministry of Culture and the German Archaeological Institute, with the support of the A. G. Leventis Foundation, initiated the restoration of the western opisthodomos by re-erecting an entire column to enhance visitors’ understanding of the temple’s scale and three-dimensional form.

A second phase, completed in 2012, focused on the comprehensive presentation of the western opisthodomos area.

Column fragments were reassembled using titanium bars, missing sections were completed with artificial stone, and the fluting was carved by hand following ancient techniques.

Today, the ruins of the Temple of Zeus invite us to imagine the awe it inspired in ancient visitors, and to remember the enduring legacy of Olympia as the birthplace of the Olympic ideal.

Visiting the Temple of Zeus remains a moving experience. As you walk among the fallen columns and the scattered blocks, you connect with a world in which humanity reached for the divine through sculpture, architecture, and ritual.

The ruins provoke reflection on how the ancient Greeks perceived greatness – in the gods, in sports, in art – and invite us to renew this relationship with the site.