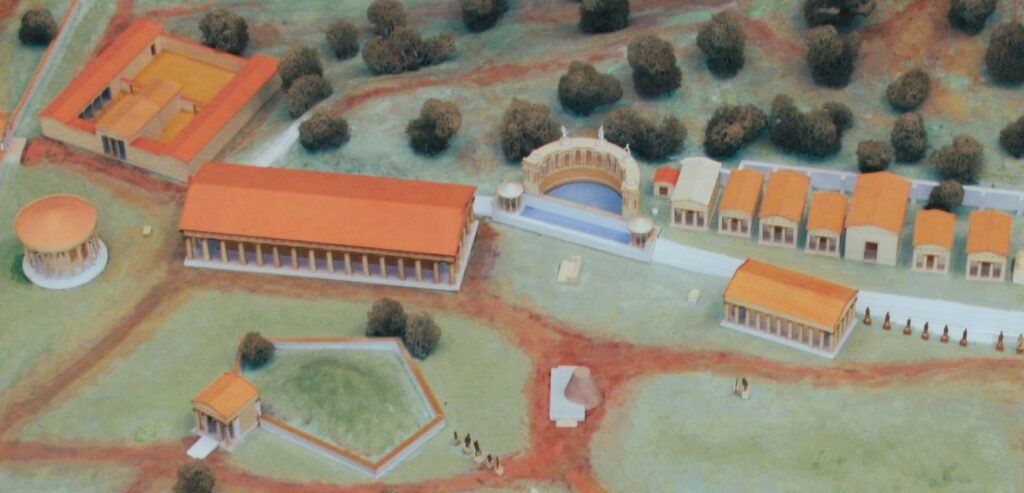

The primary function of the Nymphaion was practical. For centuries, Olympia had struggled with limited local water sources, a difficulty magnified dramatically during the Olympic Games when thousands of visitors converged on the sanctuary.

Herodes Atticus funded an intricate hydraulic system, including aqueducts, to bring a much-needed supply of pure drinking water from distant springs east of the sanctuary.

The Nymphaion itself was the glorious terminus of this system, ensuring that reliable water was finally distributed through a dense network of pipes to the entire sacred precinct. This transformation of a utilitarian necessity into a monumental act of patronage was characteristic of the Roman era.

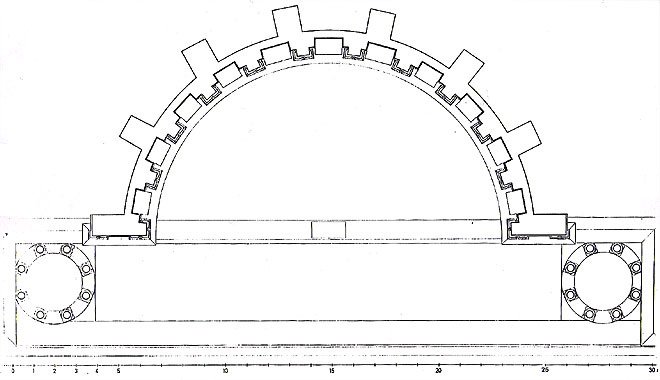

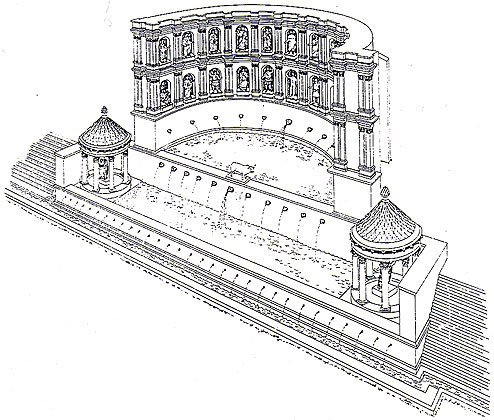

The structure’s architectural design was breathtaking in its ambition and execution. The Nymphaion featured a massive semicircular facade—an apse measuring 16.62 meters in diameter—rising in two stories and capped by a half-cupola.

The apse was originally constructed of brick and adorned with a lavish polychrome marble revetment, though little of this luxurious cladding survives today. The water flowed through the complex in a carefully orchestrated display, cascading from an upper semicircular basin into a larger, oblong tank below (21.90 meters long).

This arrangement transformed the simple act of drawing water into an architectural spectacle, blending visual spectacle with functional infrastructure.

The benefactor, Herodes Atticus, was one of the wealthiest and most cultured individuals of his era. A Roman senator of Greek origin, he was a renowned orator, intellectual, and teacher who embodied the cultural revival of the 2nd century AD, known as the Second Sophistic.

His donation to Olympia was driven by both personal piety and the competitive culture of aristocratic display prevalent among Roman elite and Hellenized Greeks.

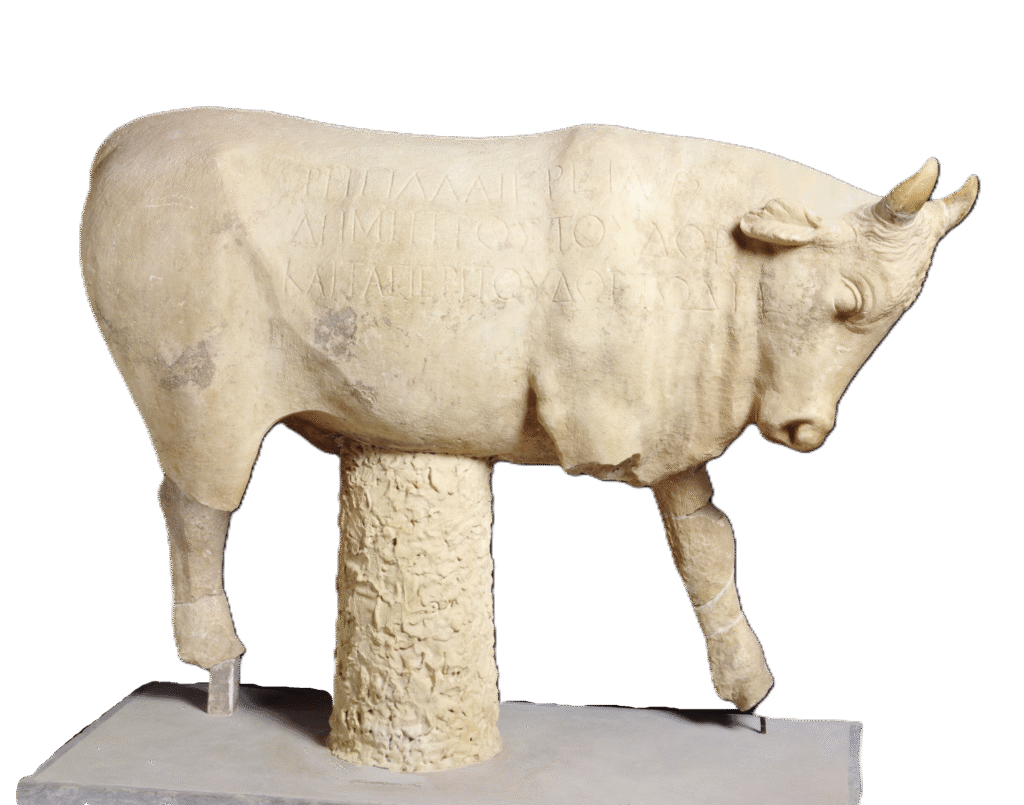

The large marble bull that once stood in the center of the main tank, bearing an inscription that recorded Herodes’s dedication of the reservoir and its statues to Zeus in the name of his wife, Regilla, who was a priestess of Demeter Chamyne.

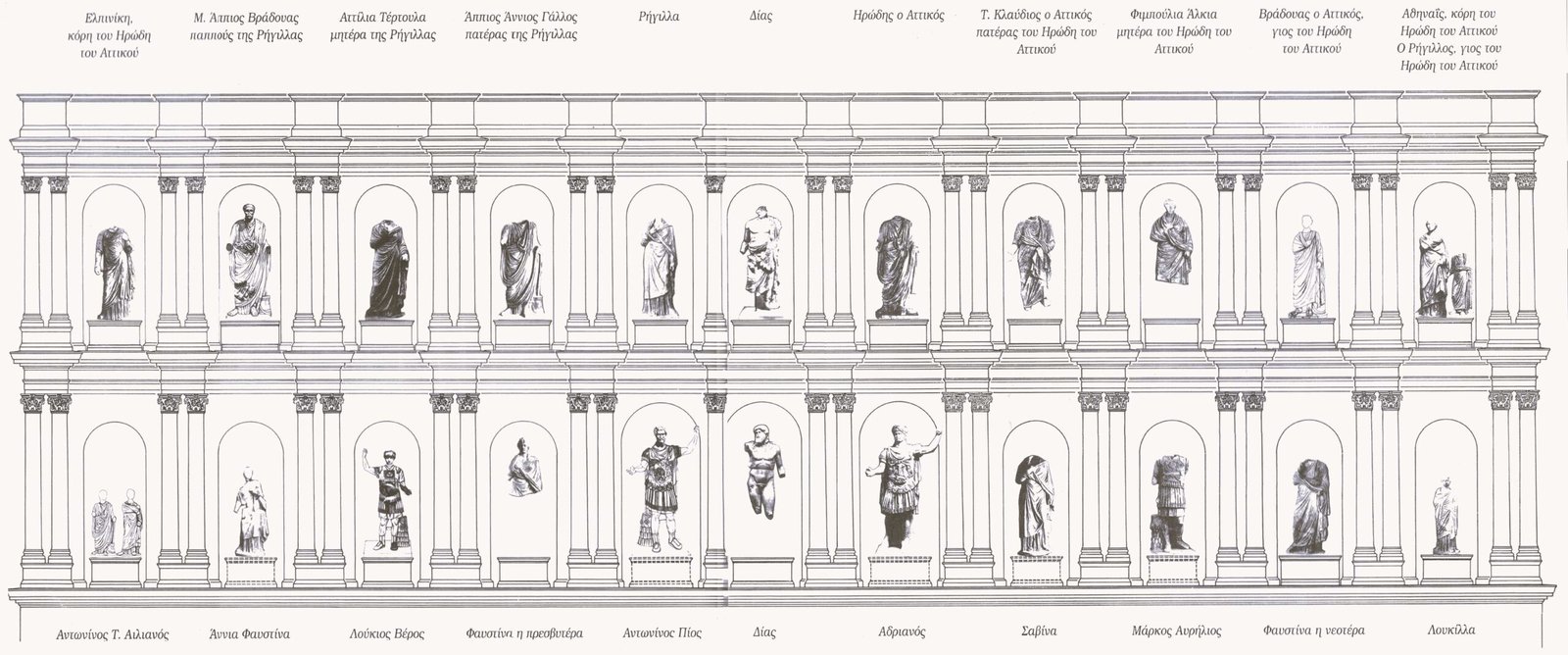

The structure housed an extensive sculptural program that communicated messages of power, lineage, and cultural identity. The apse featured two tiers of eleven niches each, populated with magnificent marble statues. The lower tier held figures representing the Roman Imperial family of Antoninus Pius, while the upper tier displayed the family of Herodes Atticus himself.

The central niche of each tier contained a statue of Zeus. Additionally, at each end of the lower oblong tank, small circular Corinthian temples enclosed statues of Herodes Atticus and a contemporary emperor (Antoninus Pius or Marcus Aurelius). This “family gallery” associated the donor’s lineage with the ultimate source of Roman imperial authority, a clear political statement.

The Nymphaion was as much an engineering achievement as it was an artistic one. Its construction required highly sophisticated hydraulic engineering to manage the water flow, maintain constant pressure for the fountain displays, and ensure a reliable, clean supply for sanctuary needs.

This technical mastery—mobilizing resources for a monumental project that solved a chronic classical problem—demonstrated the vast capabilities of Roman technical expertise. By finally providing abundant water, the system fundamentally enhanced the functionality and habitability of Olympia, especially during the massive gatherings of the Olympic festival.

The Nymphaion exemplifies how Roman-period benefactions transformed the character of Greek sacred spaces. It was a hybrid environment where traditional Greek piety met a new, dynamic Roman architectural vocabulary, engineering capability, and display culture.

Though today the structure is in a poor state of preservation, with its polychrome marble gone and architectural members re-used in a 5th-century AD Christian basilica, the surviving statues, now displayed in the Archaeological Museum of Olympia, confirm its original splendor.

The Nymphaion stands as one of the finest examples of this cultural fusion, a monument that remains a symbol of generosity and spectacular utility.