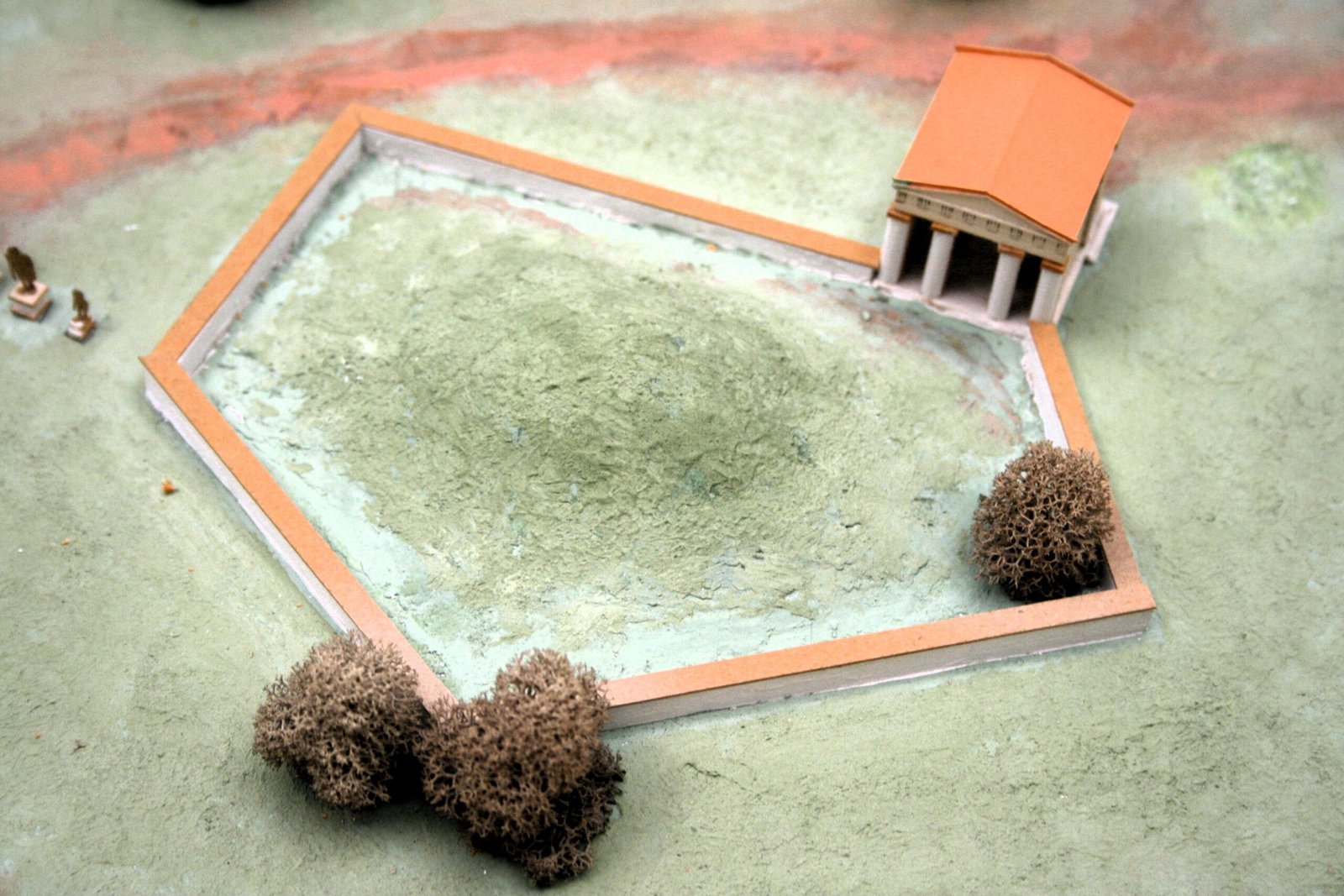

The Treasuries of Olympia lined the southern slope of the Kronios Hill in a distinctive terrace, creating one of the sanctuary’s most visually striking architectural ensembles.

These small, temple-like buildings were constructed by various Greek city-states, primarily from the wealthy colonies of Magna Graecia (southern Italy and Sicily) and other powerful polities.

Their primary function was to house valuable dedications to Zeus and display the sponsoring city’s piety and prosperity to the entire Greek world.

Dating primarily to the 6th and 5th centuries BC, the treasuries represent the sanctuary’s Archaic and Classical heyday, a period when Olympic prestige reached its peak and city-states fiercely competed to demonstrate their devotion through architectural magnificence and valuable offerings.

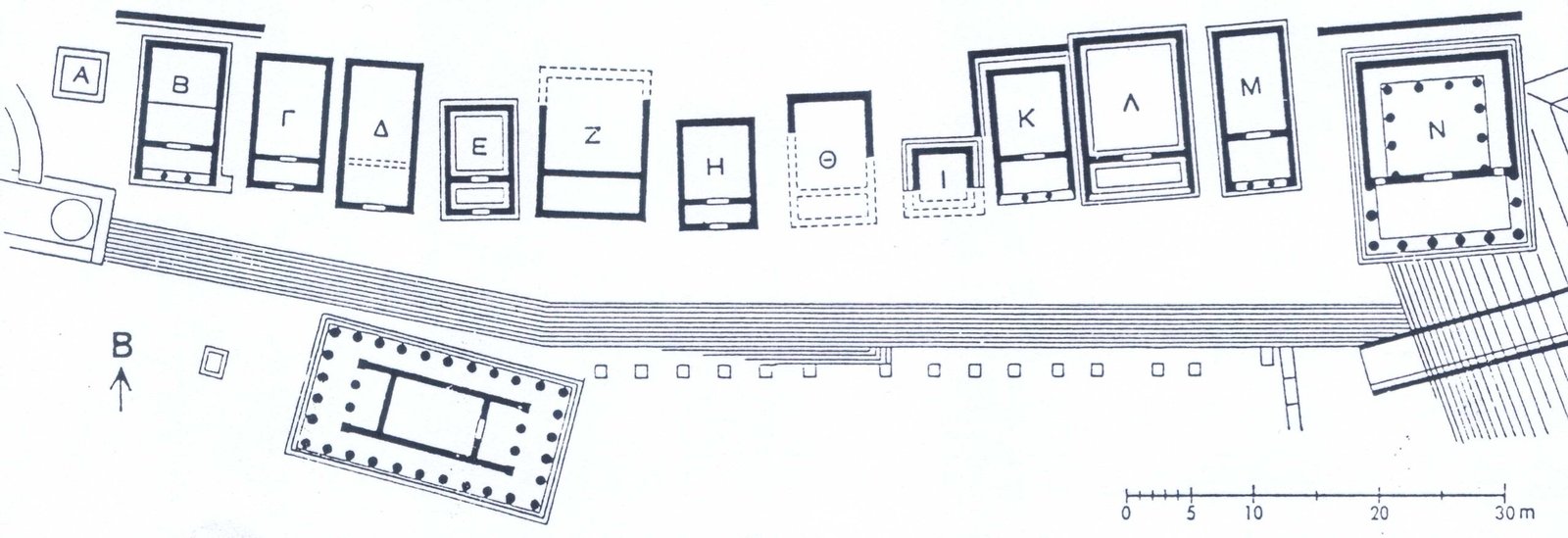

Each treasury was essentially a miniature temple in form, typically featuring a simple rectangular chamber (cella) and a porch supported by columns—often a distyle portico in antis.

The architectural style reflected the building city’s artistic preferences and regional traditions; Doric treasuries from mainland Greek cities contrasted with Ionic examples from Asia Minor colonies, fostering architectural diversity within the unified row.

Crucially, the treasuries’ facades faced outward toward the sacred Altis and the pathway leading to the stadium. This positioning ensured maximum visibility for visitors moving through the sanctuary, making the impressive array of buildings effective vehicles for civic propaganda and competitive display

Lining the southern slope of the Kronios Hill, the treasuries formed one of the sanctuary’s most visually striking architectural ensembles. Built mainly by Greek city-states from Magna Graecia and other powerful regions, these temple-like structures displayed civic wealth, piety, and prestige. Dating to the 6th and 5th centuries BC, the treasuries reflect Olympia’s Archaic and Classical height, when cities competed to honor Zeus through monumental architecture and valuable offerings.

Each treasury followed the basic layout of a miniature temple, with a rectangular cella and a columned porch, often a distyle in antis. Their architectural styles varied by the sponsoring city—Doric forms from mainland Greece contrasted with Ionic forms from eastern colonies—creating a diverse yet unified façade. Positioned to face the Altis and the path to the stadium, the treasuries were deliberately placed to maximize their visibility and propagandistic impact.

Inside the treasuries, cities stored precious offerings dedicated to Zeus: bronze and marble statues, luxury vessels, weaponry, and valuable spoils of war. These items marked military and athletic victories or economic success. Concentrating such wealth in Olympia underscored the sanctuary’s religious importance and required strict security and management.

Inscriptions on the buildings declared their sponsors and the victories or events that prompted their construction, effectively transforming treasuries into permanent public billboards. Archaeology has identified treasuries from Sikyon, Syracuse, Epidamnos, Byzantion, Sybaris, Cyrene, Selinus, Metapontion, Megara, and Gela. This wide geographic spread demonstrates Olympia’s Panhellenic identity and its role as a shared religious and political center for the Greek world.

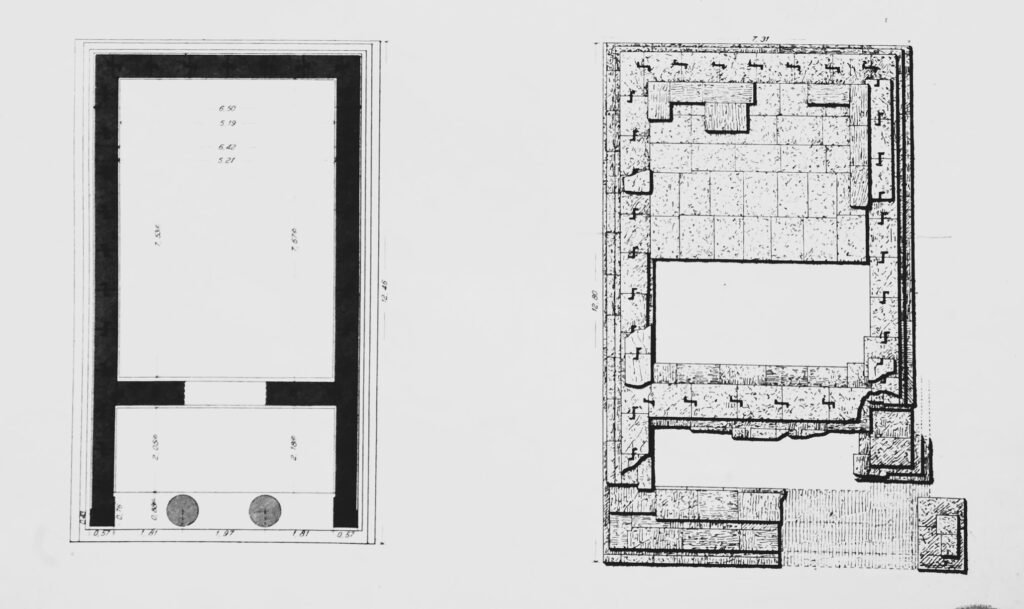

The Treasury of Sikyon was the first on the west end of the terrace and one of the earliest. Dedicated by Myron of Sikyon, it measured roughly 12.46 × 7.30 meters. Pausanias himself noted its significance. Its construction highlights the competitive drive of Greek city-states—especially those from the West—to project their cultural and political power through monumental dedications at Olympia.

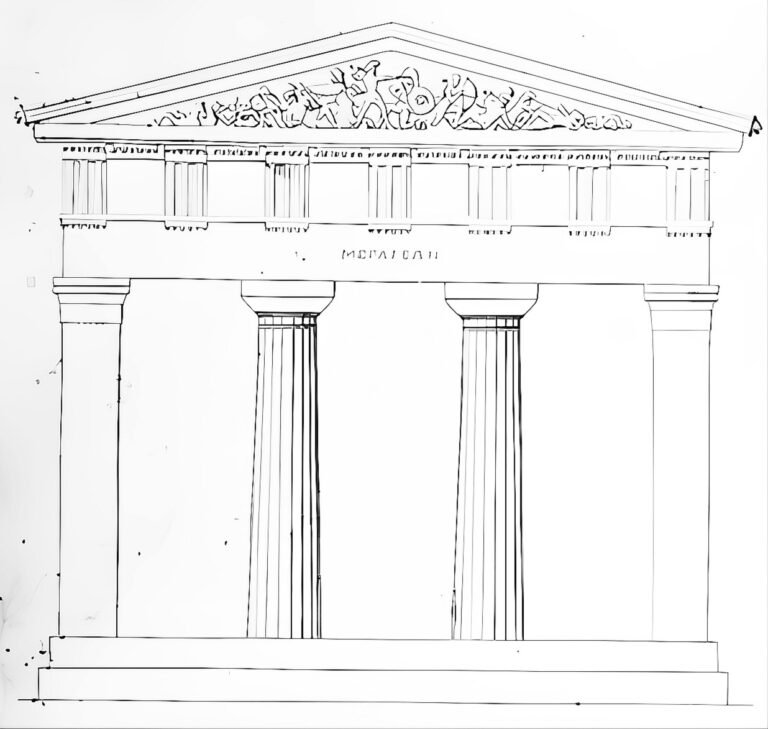

Today, visitors can still trace the outlines of the treasuries along the terrace at the base of the Kronios Hill. Excavations have uncovered numerous terracotta architectural fragments, including vividly painted pieces and acroterial groups such as a Satyr and Maenad. The restored pediment of the Treasury of Megara, depicting the Gigantomachy, now displayed in the Olympia Archaeological Museum, stands as one of the finest surviving artworks from these structures.

The treasuries housed incredibly valuable dedications, transforming them, quite literally, into treasure houses.

These offerings included bronze and marble statues, elaborate armor and weapons taken as war spoils, precious metal vessels, and other luxury items offered to Zeus by grateful cities.

The dedications often celebrated military victories, athletic triumphs, or economic prosperity. The objects represented enormous wealth, containing some of the most valuable portable items in the ancient Greek world.

This concentration of riches at Olympia both demonstrated the sanctuary’s religious importance and created inevitable security challenges, requiring guards and careful management.

Inscriptions on the treasuries identified their sponsors and frequently commemorated specific events or victories that occasioned the building’s construction.

These texts transformed the structures into permanent “billboards,” advertising cities’ achievements and piety to the thousands of visitors attending Olympic festivals.

A treasury sponsored by a colonial city, for instance, proclaimed that community’s prosperity and cultural sophistication, subtly countering potential prejudices about peripheral colonies being inferior to mainland cities.

The specific treasuries identified through archaeology and epigraphic evidence include structures from Sikyon, Syracuse, Epidamnos, Byzantion, Sybaris, Cyrene, Selinus, Metapontion, Megara, and Gela, among others.

This geographic diversity confirms Olympia’s truly Panhellenic character, serving as a central religious and political institution for all Greeks.

Among the identified structures, the Treasury of Sikyon holds distinction as the first treasury from the west and one of the earliest. It was famously dedicated by Myron of Sikyon and measured approximately 12.46 by 7.30 meters.

The importance of the city is underscored by the historian Pausanias, who specifically mentioned the Sikyon treasury in his account.

This particular dedication exemplifies the competitive spirit and investment shown by individual cities; Sikyon, like others primarily from Magna Graecia and the West, utilized the Olympic sanctuary to project its power, wealth, and cultural prominence onto a worldwide stage.

Today, the treasury terrace remains one of Olympia’s most evocative archaeological features, with the foundations and lower courses of multiple buildings still visible in their original arrangement at the foot of the Kronios hill.

Excavations yielded numerous artifacts, including a great number of terracotta architectural members with striking painted decoration, and fragments of terracotta groups, such as a Satyr and Meanad, which likely served as acroteria.

Notably, the restored pediment of the Treasury of Megara, depicting the Gigantomachy, is now displayed in the Olympia Archaeological Museum.

Walking along the terrace, visitors can appreciate the scale of ancient Greek competitive piety and the intersection of religion, politics, economics, and art that defined the Olympic sanctuary.