The Pelopion stands as a profoundly significant archaeological monument within the Altis sanctuary at Olympia, primarily serving as a tomb or cenotaph (a memorial monument for a person whose remains are elsewhere) dedicated to the local hero Pelops.

Honored particularly by the Eleans, Pelops was a figure of great local mythological and heroic importance.

According to the traveller Pausanias, the dedication of this site to Pelops was traditionally attributed to Heracles, who was believed to be his fourth descendant.

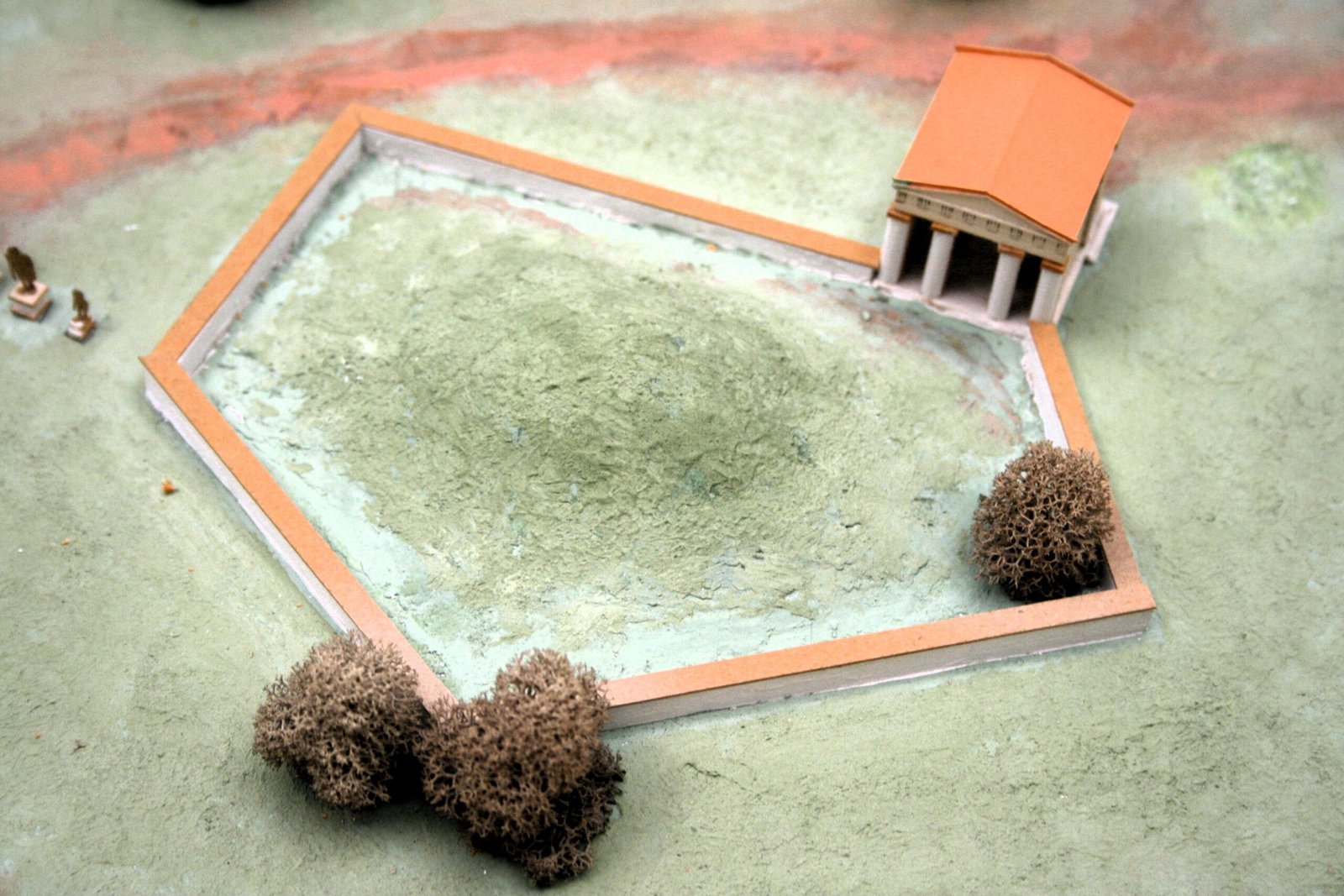

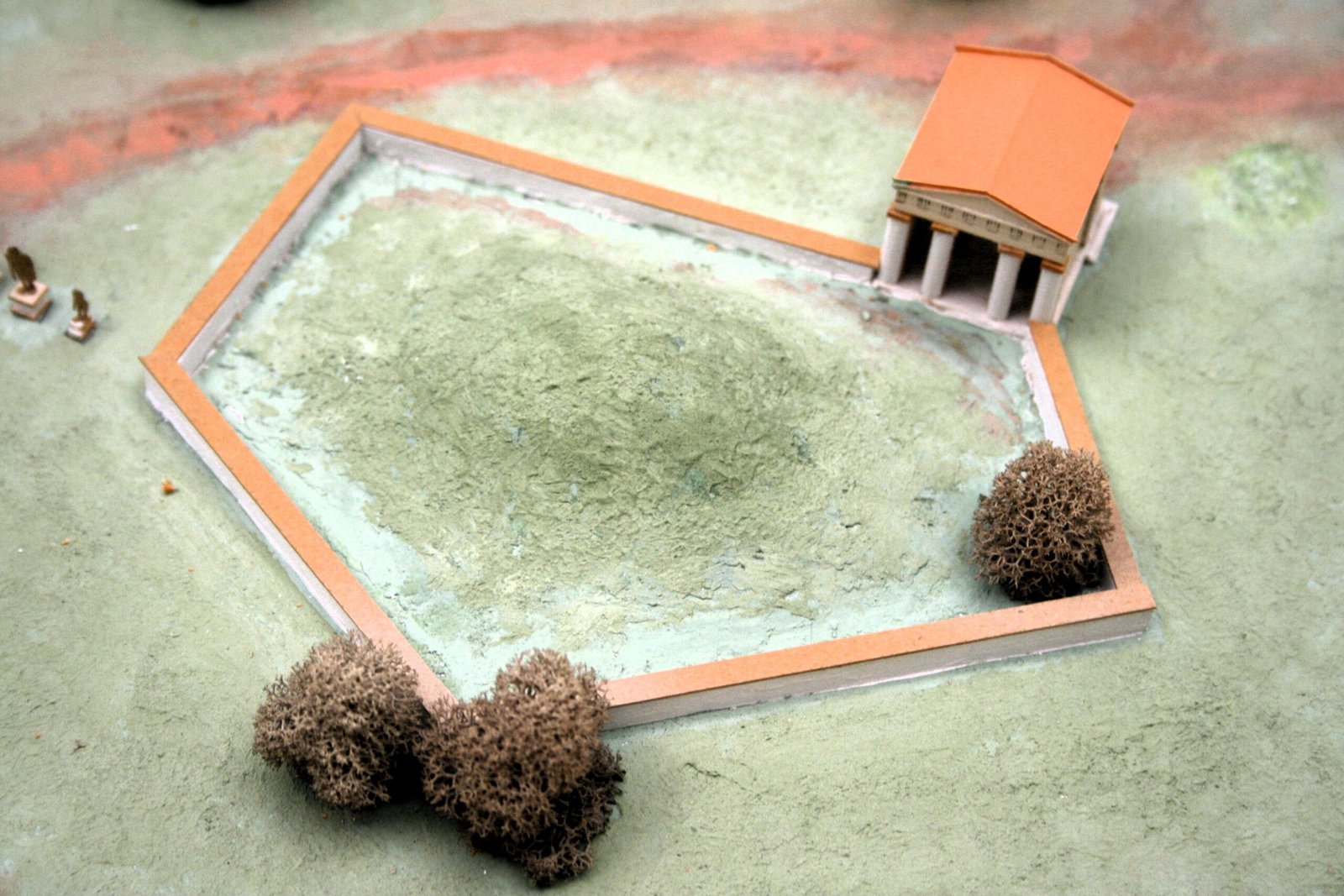

Situated prominently between the majestic Temple of Hera and the great Temple of Zeus, the Pelopion marked a key focal point within the sacred precinct.

The history of the site extends far beyond the classical era. Beneath the historical Pelopion, approximately 2.50 meters below the modern ground level, lies what is considered the oldest surviving structure within the entire Altis: a massive prehistoric tumulus. This large earthen mound, contained by a stone enclosure, dates back to the Early Helladic period (circa 2500 BC), indicating continuous sacred use of the location for millennia.

The structure recognizable in historical times was a tumulus that rose about two meters above the ground, first taking shape around the 6th century BC.

In the 5th century BC, a defined boundary was added: an enclosure built in the shape of an irregular pentagon that featured a simple entrance at its southwestern corner. This entrance was later monumentalized in the late 5th century BC with the addition of a significant stone Doric propylon (gateway), further emphasizing the importance of the sacred space.

In antiquity, the interior courtyard was adorned with trees, primarily poplars or aspens, and various statues.

The Pelopion served as a sacred tomb or cenotaph dedicated to Pelops, a hero of great local

importance to the Eleans. According to Pausanias, the monument was traditionally attributed

to Heracles, believed to be a descendant of Pelops. Positioned between the Temples of Hera

and Zeus, it formed a major focal point within the Altis sanctuary.

Beneath the visible Pelopion lies a massive Early Helladic tumulus, the oldest surviving

structure in the Altis (circa 2500 BC). This prehistoric mound, enclosed in stone, indicates

uninterrupted sacred use of the site for thousands of years.

The historical tumulus stood about two meters high and took shape in the 6th century BC.

In the 5th century BC, an irregular pentagonal enclosure with a southwestern entrance was added.

Later, a Doric stone propylon monumentalized the entrance, underscoring the site’s growing ritual

importance. The interior courtyard included trees—likely poplars or aspens—and various statues.

The Pelopion was the setting of an annual ritual in which Olympia’s magistrates sacrificed a

black ram to honor Pelops. Participants in this sacrifice were expressly forbidden from entering

the nearby Temple of Zeus, highlighting the strict separation between the hero cult of Pelops

and the worship of Zeus.

Excavations by both early and modern German missions uncovered abundant pottery, terracotta

figurines, and bronze statuettes of humans and animals. These finds illuminate the devotional

practices, beliefs, and material culture associated with the Pelopion. Many artifacts are

preserved in the Archaeological Museum of Olympia.

The Pelopion was a site of specific and unique ritualistic practice. Pausanias records that every year, the magistrates of Olympia would perform a solemn sacrifice to the hero, offering a black ram on the premises. This ritual was highly exclusive and strictly regulated.

A striking prohibition was placed upon the participants: anyone who partook in the meat of the animal sacrificed to Pelops was forbidden from entering the adjacent Temple of Zeus.

This rule underscores the distinct, yet co-existing, cults and the rigid separation maintained between the worship of the heroic ancestor Pelops and the supreme Olympian god Zeus.

Excavations conducted over time—including both older and recent German missions—have yielded a wealth of finds from the area of the Pelopion.

The discoveries include a large volume of pottery, along with numerous terracotta and bronze figurines representing both human and animal forms.

These artifacts offer invaluable insights into the devotional practices and material culture of the sanctuary throughout the ages. Many of these significant findings are now preserved and exhibited in the Archaeological Museum of Olympia