The Metroon at Ancient Olympia was a small Doric temple dating to the Classical period, originally dedicated to the Mother of the Gods, Rhea-Cybele. This deity, associated with nature, fertility, and the wild aspects of the divine, held an important place in Greek religious consciousness, representing primordial creative forces and the generative power of the earth.

The cult of Rhea-Cybele, particularly in its more ecstatic forms, represented aspects of religious experience quite different from the ordered, civic religiosity associated with Olympic Zeus. Worshippers of the Mother Goddess sometimes engaged in more emotional, mystical practices, and the goddess’s associations with wild nature and transformative power offered religious experiences complementary to the formal state rituals of the Olympic festival. The Metroon thus added religious diversity to the sanctuary, acknowledging that pilgrims came to Olympia with varied spiritual needs and devotional preferences.

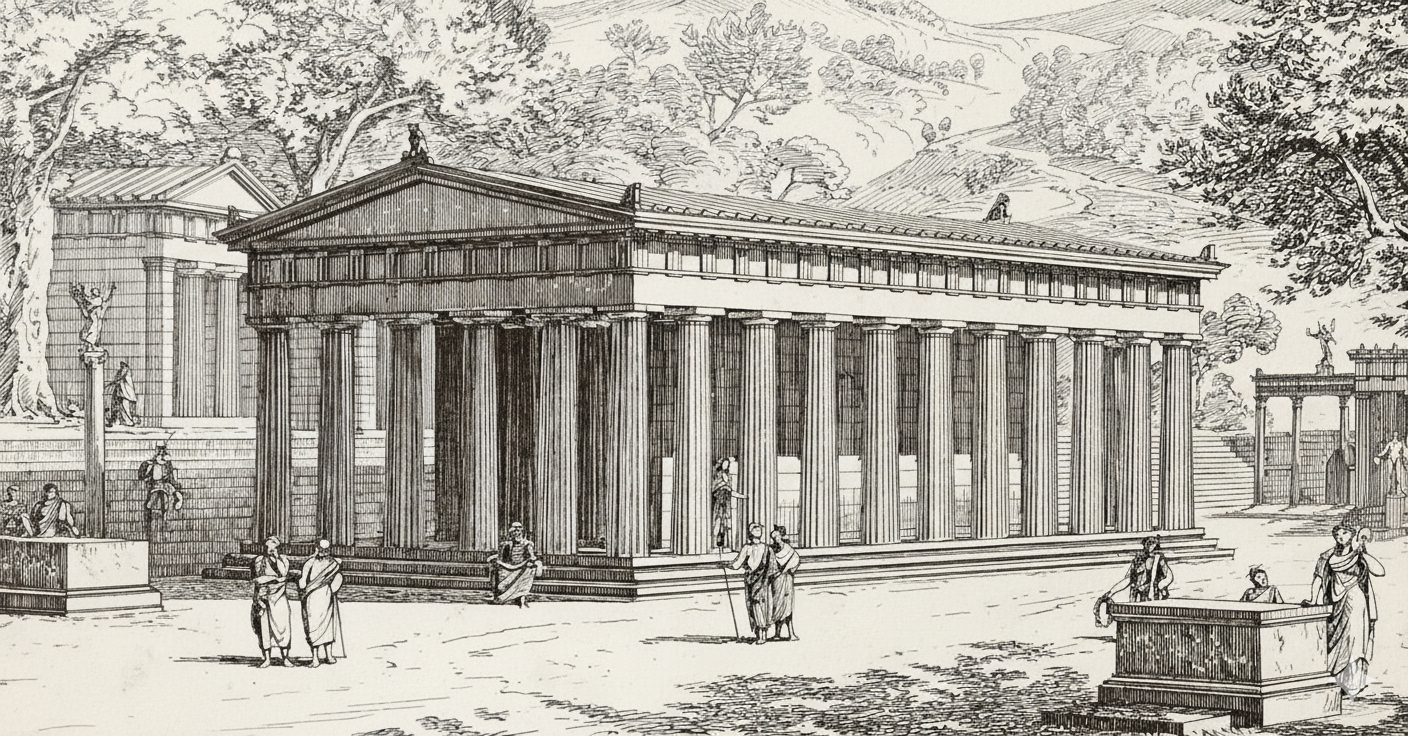

The temple’s relatively modest dimensions—especially compared to the monumental temples of Zeus and Hera—reflected the goddess’s specific religious role within the Olympic sanctuary’s complex theological landscape. It stood on the terrace below the Treasuries, in a location that was prominent yet distinct from the central edifices dedicated to Zeus and Hera. This positioning reflected the Metroon’s role as a significant but secondary cult place, serving worshippers drawn to the Mother Goddess while remaining subordinate to the sanctuary’s primary divine patrons.

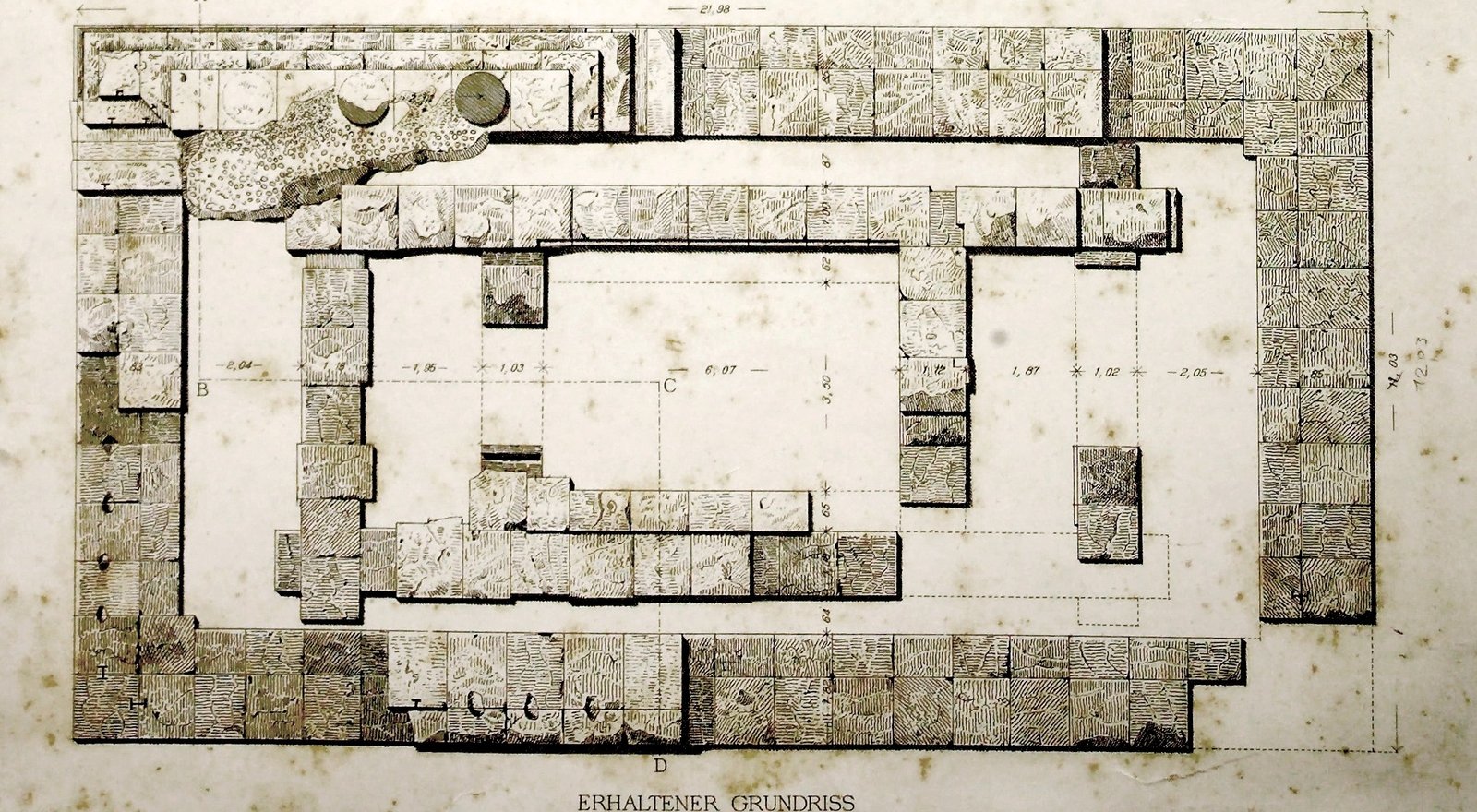

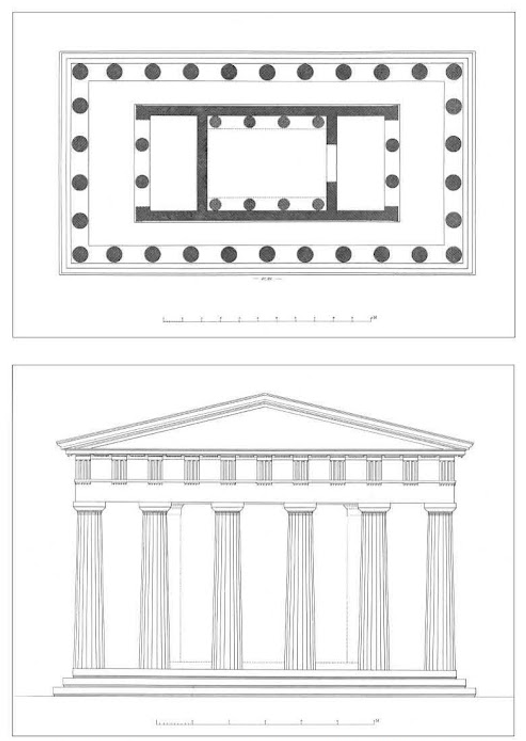

The architectural design of the Metroon followed traditional Doric temple forms with six columns on the short ends and eleven along the sides, creating a peristyle structure of elegant proportions.

Built primarily from shell-limestone finished with white plaster, the temple featured columns that stood 4.63 meters tall. Its interior layout was classic, comprising three chambers: the pronaos, cella, and opisthodomos.

Plastic Decoration

The decoration of the temple included architectural sculptures as well as a unique collection of statues inside:

• Metopes: The original temple had stone metopes above the pronaos and the opisthodomos. During the Roman renovation, these were removed and replaced by stucco decoration.

• Pediments: Research has suggested that a marble statue of Dionysus, found in the area, belonged to the eastern pediment of the temple and dates to the early 4th century BC.

Both the front and rear porches were secured by two columns set between the projecting walls (distyle in antis). The upper stone elements included the architrave and triglyph-metope frieze, supporting a timber roof covered in tiles.

It is unknown whether the cella contained an interior colonnade. The altar dedicated to Rhea was probably located either directly to the west or higher up with the treasuries.

During the Roman period, the Metroon underwent a significant transformation in function, being rededicated to the cult of the emperors—the imperial cult that became central to Roman religious-political practice.

This repurposing of Greek religious structures for emperor worship was common throughout the Roman Empire, as conquerors sought to integrate themselves into existing sacred landscapes while maintaining continuity with local religious traditions.

The Metroon’s conversion reflected Olympia’s adaptation to Roman rule and the sanctuary’s continued importance in the imperial period.

The temple’s survival in modified form through the Roman period demonstrates both the adaptability of ancient religious structures and the pragmatic Roman approach to conquered territories. Rather than destroying Greek religious buildings, Romans often repurposed them, creating continuity while asserting imperial authority.

The Metroon’s transformation from a temple of the Mother Goddess to an imperial cult center exemplifies this strategy, maintaining the building’s sacred character while redirecting worship toward new objects of veneration.

With the Metroon’s rededication, the inner sanctuary (sekos) was furnished with monumental statues dedicated to the emperors.

The most significant of these was a monumental cult statue of an emperor represented as Zeus holding a thunderbolt and sceptre. This deliberate visual association merged the power of the Roman ruler with the supreme authority of the Olympic god, further asserting Roman dominance and integrating the imperial cult into the local divine hierarchy. This statue is now a major exhibit in the Olympia Archaeological Museum.

In addition to this central figure, six more imperial statues were discovered during excavation—three male and three female. These are believed to represent members of the Flavian dynasty and their close relatives, specifically: Claudius, Titus, Vespasian, Agrippina, and Domitia. The presence of these multiple statues within the Metroon underscores the temple’s new role as the primary center for imperial veneration at the sanctuary, transforming its function from celebrating a primordial Greek goddess to affirming the contemporary political and religious authority of the Roman Empire.

The temple suffered serious damage during the Heruli invasion (3rd century AD) and was later demolished. Its architectural elements were reused for the construction of the defensive wall of Olympia in the 5th or 6th century AD.